I was an outlier for as long as I can remember. In my high school I had a small circle of friends; in gym class I was picked last. I was bullied—briefly—and today I’m actually friends with the boy who did it. It turned out he was an outlier too.

Since early childhood I showed traits not typical of a young boy, and I was aware enough to notice. I come from a Reformed Lutheran church. When I was about ten or twelve, I saw a typical evangelical service and it felt heavy. I remember saying: “This reformed church should have been reformed.”

Around the same age I also received my first visions. I remember one dream in particular: I wanted to fly a helicopter, but as a child that wasn’t an option. One night I dreamed of a remote‑controlled model helicopter with a camera attached to it, and I watched the feed on a CRT TV on the ground. Yes, it was a dream—but what I pictured is what we today call drones. It wasn’t a helicopter with a camera, but the concept was there, and today it’s a multibillion‑dollar business. There was a problem, though: I was just twelve. I had the dream, but I wasn’t capable of making it a reality.

When I started university, I stopped dreaming. Most nights were blank, as if something in me were blocked. I focused on my studies, later on my career, and I forgot to dream—until recently, when I left the corporate world and my dreams returned even stronger.

My grandfather was a born leader. From my mother’s stories I know how proud he was to have a grandchild—a boy. He had four daughters and not a single son. My grandpa loved me. That started to shift when I began speaking, and it definitely changed when I began thinking. My grandpa loved to give orders: do this; hold this for me. And the four‑year‑old me asked “why”? Why do I have to do this? Why does that thing work? One of our last big projects together was crafting a homemade TV antenna. In the old days you couldn’t just buy one, so you made one from wire. By the way, I later studied telecommunications, and I love antennas to this day.

My grandfather could have taught me a lot, but he wasn’t patient. He was used to obedient people, and I was different. I couldn’t articulate it back then, but now I know better—I was a sovereign, curious child and a natural alpha. Not the chest‑beating status kind, but the kind that stands his ground and stays curious. I still am in 2025. Given my grandfather lost patience with me, I learned from others. Just observing craftsmen is enough for me to replicate; YouTube also helped. A few years ago I started a long‑term collaboration with my cousin, and he taught me electronics.

I am a rare breed. In a world obsessed with specialization, I had a problem. I have a proven track record of having many talents. Usually, whatever I decide to do, I quickly become good enough to get paid for it. This has a cost, and I’ll use my favorite quote from the movie Charlatan:

Nejtěžší trest je možnost volby. (The most severe punishment is the freedom of choice.)

People with one talent—or barely one—paradoxically have it easier. They pick the thing they’re good at and make it their career. I struggled for more than ten years trying to figure out what I wanted to do. Only recently did I realize I want to be a movie director.

My biggest weakness has been physical coordination. Strong mind, weaker body. But because it’s me, I love challenges—I purposely do things where I’m the worst. Books say: focus on your strengths; the effect will multiply. I do the opposite because I care less about maximization and more about becoming whole.

You can probably tell by now that I have an analytical mind. Well, there is more. I play the accordion; I am naturally good at foreign languages; I love searching for hidden layers in art—movies, books, poems. With some training I could probably sing, too. I was among the best students at university, and I’m almost certain I could hold my own in a philharmonic orchestra.

In a world of specialists, I am a generalist.

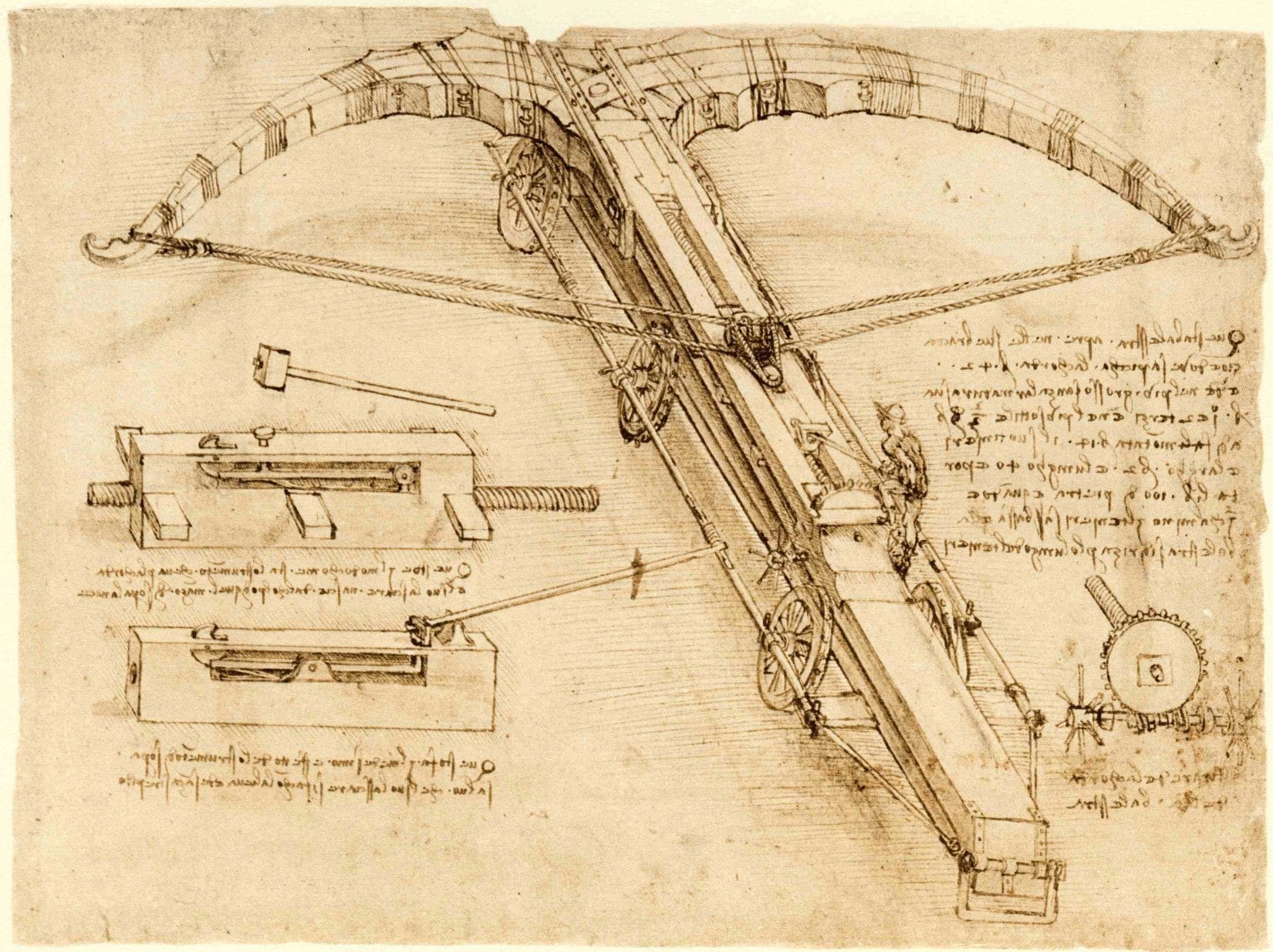

I am the modern Renaissance man.

People envy Elon Musk his billions. He once said, “There is a storm in my head. You wouldn’t last in my head for five minutes.”

While I cannot compare his storm to mine, I am one of the few who get it. Being someone like me is a gift and a curse, as Adrian Monk used to say.

Because I choose to look at the world positively, I’ve decided to treat my mind as the greatest gift I have and to share it with the world. The realm for outliers is my gift to you.

For quite some time I have felt close to giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Nikola Tesla, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Steve Jobs, and Walt Disney. This is not bragging. Do you realize what it’s like to discover that I’m just a boy from a modest family, raised in an “insignificant” country somewhere in Central Europe—and that I might achieve big things? Something that might shift our society for the better? I questioned myself. Is it real? Can it truly be that I’m someone like Disney from Europe? Why me? The truth is, after studying their lives, I saw they had the same doubts I have now. Nikola Tesla worked on his inventions, unsure whether he was on the right track. He just followed his passion and died poor. Disney had a dream and followed it. And I, in 2025, have dreams as big as theirs.

For a while, I wondered whether I might be on the autism spectrum. I even read a book. I have some traits that look similar. When I think about a problem, I have tunnel vision—I literally don’t see the people around me. A friend asks me, “Did you see that hot woman?” and I reply, “No, I didn’t.” I am a dreamer. Visionaries often drift with their minds to the skies and ignore mundane things like traffic. I find most people boring, and I naturally attract outliers with very high IQs. It’s statistically improbable, but it happens.

Why did I eventually conclude that I’m not autistic? One small thing: the way I experience empathy. I read people better than they read themselves, and I genuinely feel their pain. I can cry just by watching a romantic movie. I’m not pretending the tears or the feelings. I am logical, and I am a being with deep feelings. I am an anomaly.

There might not be a box for people like me. The closest term I’ve found is neuroatypical. It has its pros; it has many cons; but at the end of the day this is me, and I wouldn’t change my life for anything.

We are sent to Earth, and it’s a gift. Someone is born in a poorer country; someone like me gets an unusual brain—but it’s still a life worth living. My mission is clear: find more outliers at least somewhat similar to me, because I love having them as my friends. Are you one of them? Maybe one day we will meet in my realm. Until then, thank you for reading!